Part 3: When Neutral Isn’t Negative: What “Neither Fair Nor Unfair” Really Means

In conversations about money and relationships, we often assume opinions fall neatly into two camps: fair or unfair, good or bad, working or broken.

But the data tells a more complicated story.

In our survey of 700 cohabiting adults in the United States, a substantial portion of respondents described their expense-sharing arrangement as “neither fair nor unfair.” Not dissatisfied. Not content. Just neutral.

At first glance, neutrality can look like indifference. But in the context of shared finances, it may signal something else entirely.

The Size of the Neutral Middle

Across multiple expense-splitting arrangements—from 50/50 splits to situations where one partner pays most or all shared expenses—neutral responses appeared consistently.

This matters for two reasons:

Neutrality wasn’t confined to any single arrangement

It represented a meaningful share of responses, not statistical noise

In other words, neutrality isn’t a fringe reaction. It’s a common one.

Which raises a question we don’t often ask:

What does it mean when people don’t label their arrangement as fair or unfair?

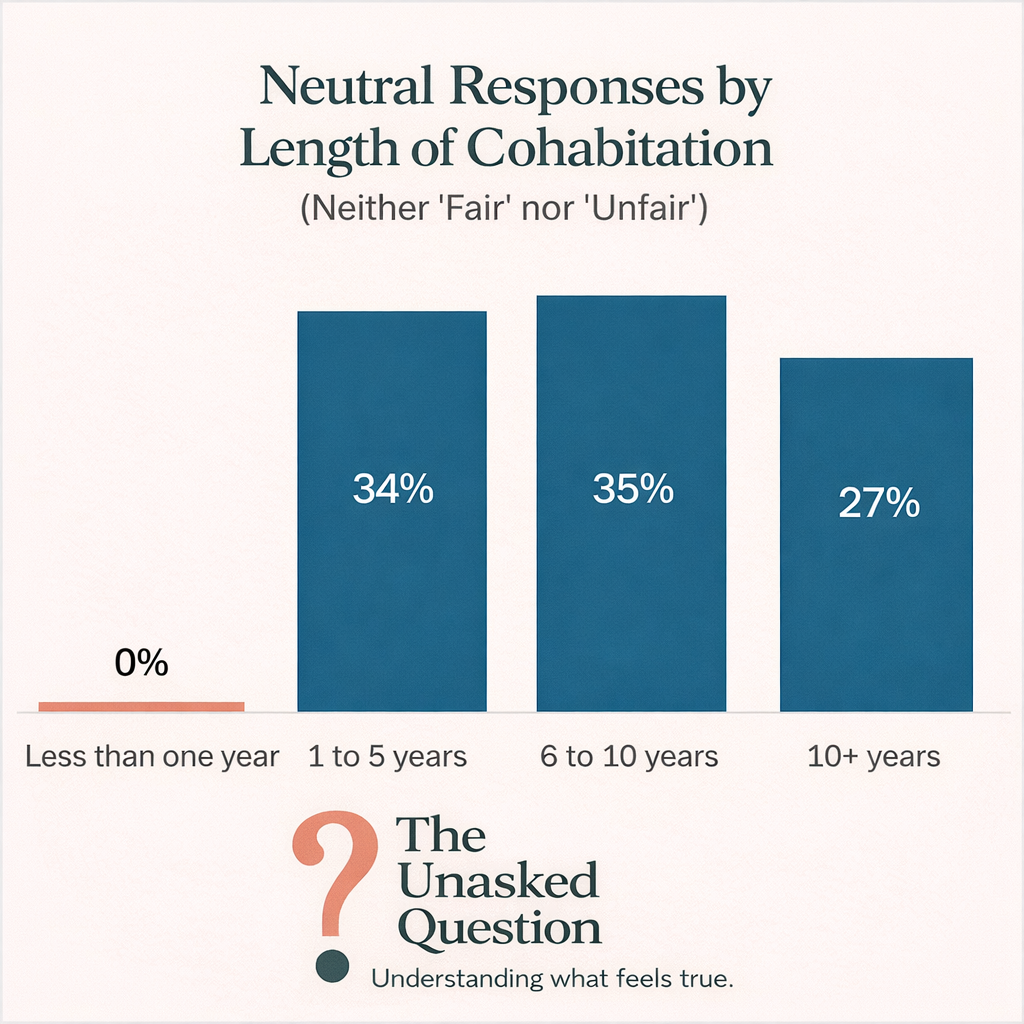

Neutrality Over Time: Not a Phase

One assumption might be that neutrality reflects uncertainty—something common early in relationships that fades as couples settle into clearer opinions.

But the data doesn’t support that.

When we examined neutral responses by length of relationship and length of cohabitation, neutrality persisted across time. Couples together for 1–5 years, 6–10 years, and even more than a decade reported neutrality at similar rates.

Neutrality, it turns out, is not something couples necessarily “grow out of.”

This suggests that neutral isn’t a temporary state on the way to fair or unfair. For many couples, it appears to be a stable equilibrium.

Neutral as Stability, Not Apathy

One interpretation is that neutrality reflects stability rather than satisfaction.

Many couples may not evaluate their financial arrangements in emotional terms at all—at least not regularly. If the bills are paid and conflict is low, the system fades into the background of daily life.

Neutrality, in this sense, may mean:

“It works.”

“We don’t argue about it.”

“There are bigger things to worry about.”

That doesn’t imply enthusiasm—but it does suggest adequacy.

Neutral as Adaptation

Another possibility is adaptation.

Over time, people tend to adjust their expectations to match their circumstances. What once felt temporary can become permanent. What once felt imbalanced can begin to feel normal.

Neutral responses may reflect:

Arrangements that evolved gradually without explicit agreement

Systems people wouldn’t actively choose—but also wouldn’t change

A quiet recalibration of what “fair” means in practice

This doesn’t mean people are unhappy. It means they’ve adapted.

Neutral as Avoidance

There’s also a more uncomfortable interpretation.

Labeling something as unfair can invite conflict—or require action. Neutrality may offer a way to avoid both.

Saying “neither fair nor unfair” can function as a buffer:

Against difficult conversations

Against acknowledging dissatisfaction

Against reopening settled dynamics

In that sense, neutrality isn’t passive. It’s protective.

Why Neutrality Deserves Attention

Neutral responses are easy to overlook because they don’t demand intervention. But they often mark the space where unexamined systems live.

This matters because:

Neutral arrangements are rarely discussed

They can persist for years without reassessment

They’re often the hardest to revisit once they stop working

By the time neutrality turns into dissatisfaction, the arrangement may already feel entrenched.

Rethinking Fairness

The presence of a large, persistent neutral group suggests that fairness may not be a binary judgment. Instead, it may operate along a spectrum that includes:

Satisfaction

Acceptance

Tolerance

Avoidance

Neutrality sits in the middle of that spectrum—not as a failure, but as a signal.

The Unasked Question

Neutrality, it turns out, is not a temporary state for many couples. It persists across years of relationships and cohabitation, suggesting that acceptance—rather than evaluation—may be doing much of the work.

If couples can live comfortably with arrangements that aren’t clearly fair or unfair, then the real story may not be about individual expense splits at all—but about how people learn to live with imbalance, and when they stop questioning it.

And perhaps more importantly:

At what point does “it’s fine” become “we never revisited it”?

—

This article is part of an ongoing series by The Unasked Question, examining the everyday systems we accept without scrutiny—and what happens when we pause to look more closely.