Part 2: Why Proportional-to-Income Splits Underperform in Practice

Among advice columns, personal finance blogs, and relationship forums, one recommendation appears again and again: split shared expenses proportionally to income.

On paper, it makes sense. If one partner earns more, they contribute more. The math is clean. The logic feels fair.

But in our survey of 700 cohabiting adults in the United States, proportional-to-income splits ranked lowest among common expense-sharing arrangements when respondents were asked whether their setup felt fair.

That doesn’t mean proportional splits fail outright. It does suggest something more interesting: what feels fair in theory doesn’t always translate into lived experience.

The Data Point That Raises Questions

When respondents rated their arrangements as “Very fair” or “Somewhat fair,” proportional-to-income splits trailed every other model we tested—including situations where one partner paid most or all shared expenses.

At first glance, this result seems counterintuitive. Proportional splits are often framed as the most equitable option available.

But a closer look at the data complicates that narrative.

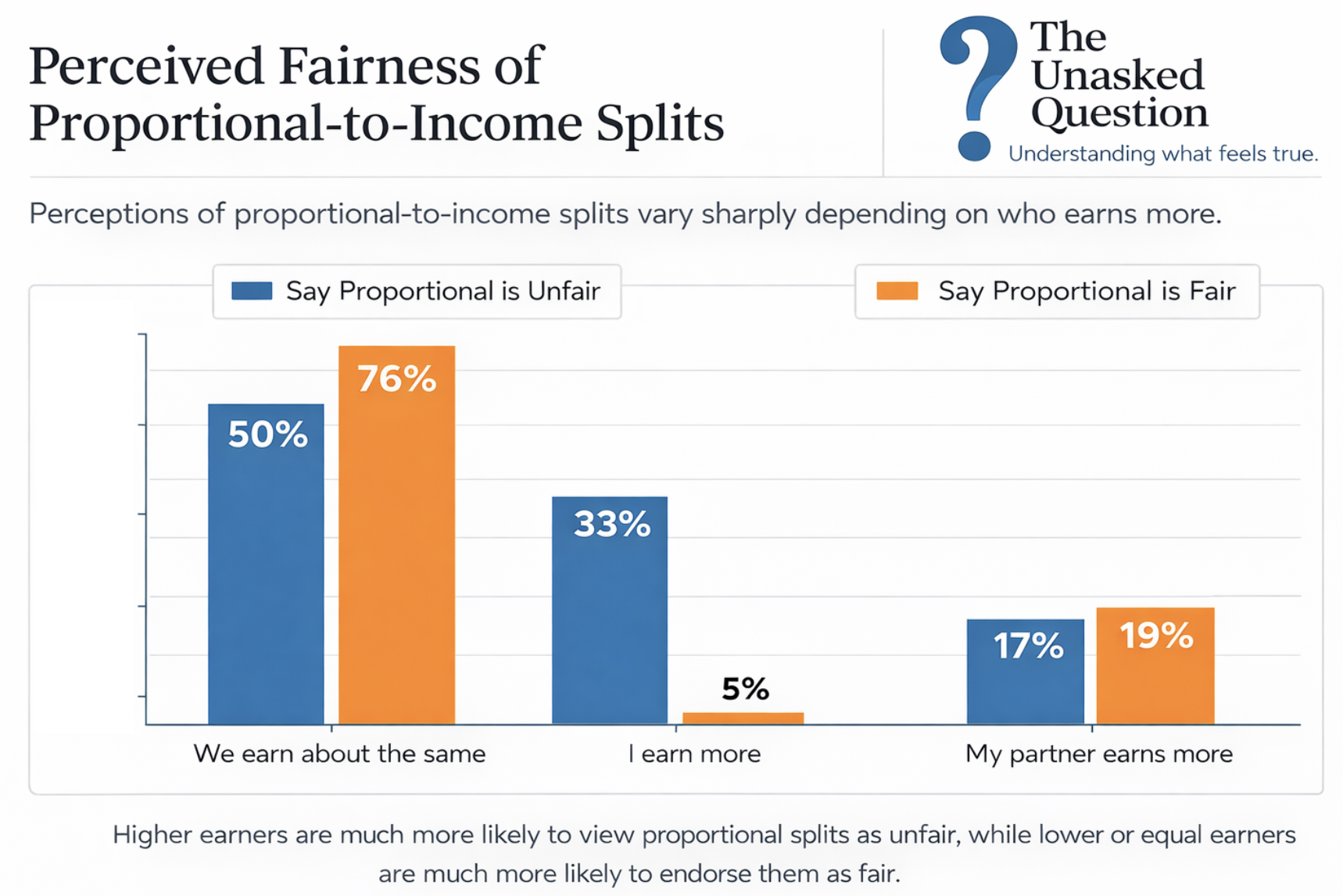

Among respondents who used proportional splits and said the arrangement felt fair, fewer than 5% reported earning more than their partner. Most earned about the same—or less.

By contrast, among those who said proportional splits felt unfair, one-third were the higher earner.

This suggests that perceptions of fairness shift sharply depending on where someone sits within the ratio itself.

The Difference Between Logical and Emotional Fairness

Proportional splits appeal to logic. They aim to correct imbalance by aligning contribution with income.

But relationships aren’t managed in spreadsheets.

In practice, proportional systems introduce questions that don’t have obvious answers:

Which income counts—gross or net?

How are bonuses, debt, or unstable earnings treated?

What happens when incomes change?

Does paying more feel like responsibility—or obligation?

These questions don’t disappear once the split is set. They linger, often unspoken.

Visibility Can Cut Both Ways

One unintended effect of proportional systems is heightened visibility.

When contributions are explicitly tied to income, the imbalance becomes harder to ignore. Each payment can feel like a reminder of who earns more, who pays more, and why.

For some couples, that transparency is empowering. For others, it creates friction:

Guilt for the lower-earning partner

Resentment for the higher-earning partner

A sense that financial roles are being constantly evaluated

Ironically, a system designed to feel fair can feel more emotionally loaded than simpler arrangements.

When “Fair” Feels Like Accounting

Another possibility is that proportional splits feel less like partnership and more like calculation.

Many couples may prefer arrangements that:

Feel stable over time

Require less ongoing adjustment

Fade into the background of daily life

Proportional systems often demand regular recalibration. That can make the financial relationship feel transactional rather than shared—even when intentions are good.

The Role of Expectations

It’s also worth considering expectations.

Because proportional splits are so often described as the “fairest” option, couples who choose them may hold higher standards. When the arrangement doesn’t deliver emotional ease along with mathematical equity, disappointment can follow.

In contrast, simpler or less explicitly “fair” systems may benefit from lower expectations—and therefore feel more acceptable in practice.

Rethinking What Underperformance Means

To be clear, this isn’t an argument against proportional-to-income splits.

For many couples, they work well.

But the data suggests they are not universally experienced as the fairest option, despite their popularity in theory.

That gap between recommendation and experience is worth paying attention to.

The Unasked Question

The gap between what seems fair in theory and what feels fair in practice highlights something important: people don’t experience financial arrangements as formulas.

But not everyone responds to that tension with dissatisfaction. In fact, many respondents didn’t describe their arrangements as fair or unfair at all.

Instead, they chose something quieter—and harder to interpret:

What does neutrality mean?

—

This article is part of an ongoing series by The Unasked Question, examining the everyday systems we’re told are “best”—and what actually happens when people live with them.