Part 4: Unequal but Fair: What This Series Reveals About Financial Imbalance

By the end of this series, one pattern becomes hard to ignore.

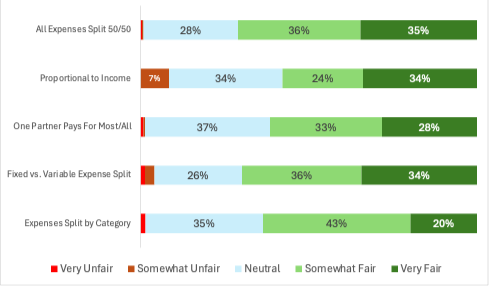

Across every expense-splitting arrangement we examined—50/50, proportional to income, one partner paying more, fixed versus variable, category-based—the same outcome appeared again and again:

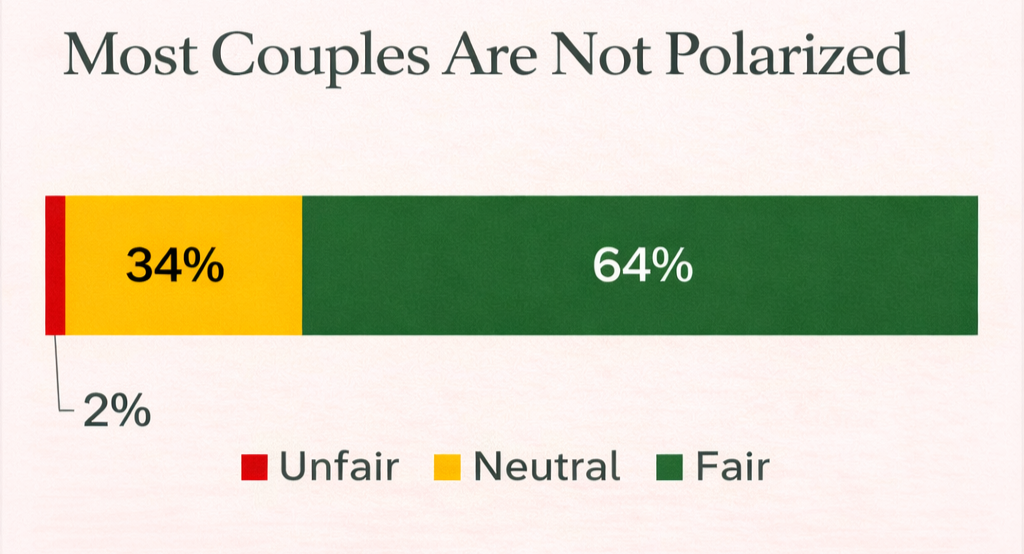

Most couples did not cluster at the extremes.

They didn’t describe their arrangements as clearly fair or clearly unfair. Instead, responses spread across a wide middle—marked by neutrality, moderate approval, or quiet acceptance.

This matters, because most conversations about money in relationships assume polarization. We tend to frame financial dynamics as problems to solve or conflicts to resolve. Either something is working—or it isn’t.

Yes, splitting expenses evenly ranked highest when respondents were asked which arrangements felt fair. But the margin was narrow. And more striking still, over 60% of respondents said it felt fair when one partner paid most or all shared expenses.

At first glance, that result seems contradictory. If fairness is about balance, how can imbalance feel fair?

The data suggests that to understand fairness, we have to look beyond the numbers.

What the Numbers Don’t Capture

In theory, unequal expense splits are often framed as a temporary solution or a problem to be fixed. In practice, many couples appear comfortable living with them—sometimes for years.

That comfort likely comes from factors that don’t appear on a spreadsheet:

Differences in time, labor, or caregiving

Assumptions about responsibility or security

Clear (or long-standing) expectations

Arrangements that evolved gradually and were never formally revisited

None of these dynamics are inherently fair or unfair on their own. What matters is that, for many couples, imbalance does not automatically register as injustice.

Equality vs. Acceptance

One of the clearest patterns across the data wasn’t equality—it was acceptance.

Couples using very different financial models reported similar levels of perceived fairness. That points to a central takeaway from this series:

Fairness seems to depend less on the structure of an arrangement and more on whether both partners accept it.

Sometimes that acceptance comes from open discussion. Other times, it comes from habit, silence, or the simple desire to avoid conflict. Over time, arrangements that begin as practical solutions can harden into defaults—“the way things are”—even if they no longer feel ideal.

The Neutral Middle

The large number of neutral responses in the survey reinforces this idea. Many respondents weren’t enthusiastic about their arrangements, but they weren’t unhappy either. They were simply okay.

That neutral space—between satisfaction and dissatisfaction—is where many financial systems quietly live. It’s also where they’re least likely to be examined.

Why This Matters

Money in relationships is rarely just money. It intersects with:

Power

Responsibility

Security

Identity

When one partner pays more, the question isn’t only how much. It’s why, since when, and with what expectations attached. Those questions don’t always surface immediately—but they shape how arrangements are experienced over time.

Understanding this helps explain why unequal systems can persist without obvious conflict—and why they can become difficult to revisit once they’re established.

The Unasked Question

Taken together, this series suggests that the most important question may not be how couples should divide expenses, but something quieter and harder to answer:

What makes an arrangement feel fair enough to live with?

And just as importantly:

At what point does acceptance turn into assumption?

—

This concludes our initial series by The Unasked Question, examining the everyday systems we rarely scrutinize—until they stop working.